Chitpur Memory Game was a community engagement project initiated in 2015. Supported by Hamdasti, it was first presented at the Chitpur Local festival in the same year.

Chitpur is the oldest road in Kolkata. In its prime, Chitpur’s palatial houses were juxtaposed with bustees, and its historic centres of Bengal Renaissance culture coexisted with the more colloquial centres of cultural production like the Bottola publishing hub and the Jatra para (vernacular theatre locality).

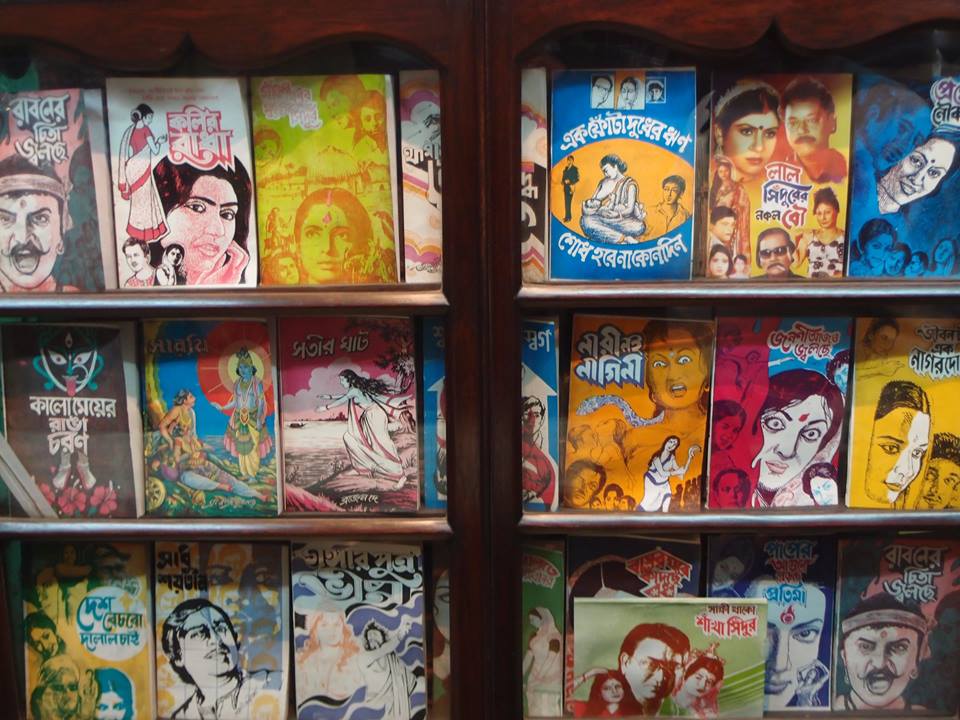

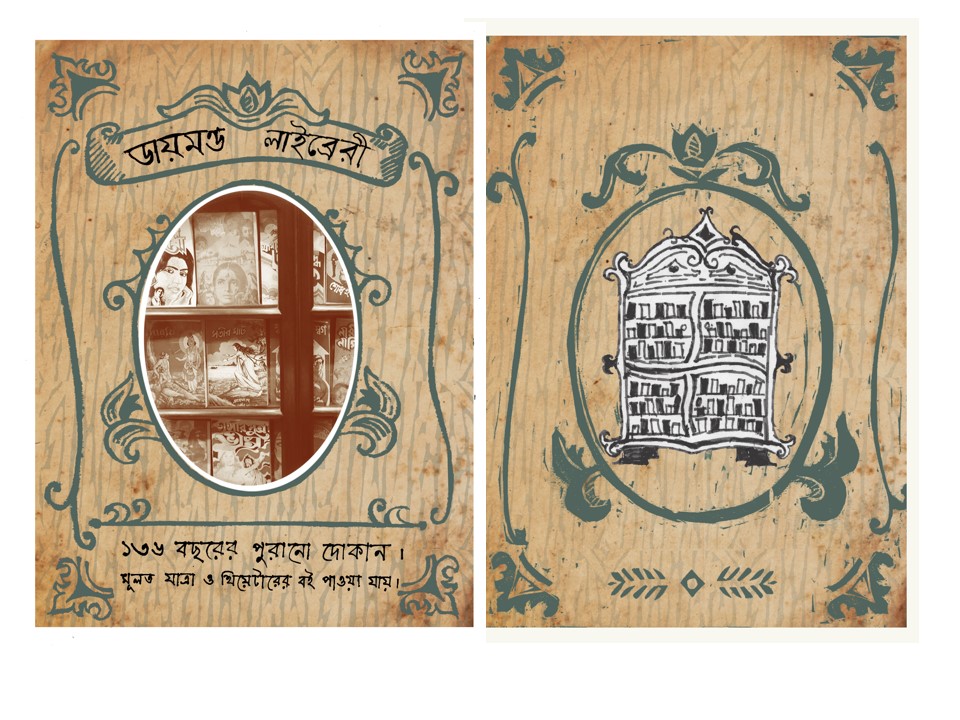

In the mid-19th century, several indigenous presses came into existence in Bengal. Chitpur, in North Calcutta, saw the emergence of a vernacular printing industry. Illustrated literature, stories, magazines, and textbooks began to be published. The use of wood engraving by indigenous artists cropped up in these publications as illustrations, “which may be regarded as the first step towards the commencement of artistic printmaking”. ‘Oonoodha Mongal’ is the first illustrated Bengali book published in Calcutta in 1816, featuring four wood engravings in a heavy, ponderous style by an anonymous engraver. Subsequently, in 1830 the first Bengali illustrated magazine, ‘Pashwabali’ or Animal Biography was published, containing six animal illustrations in a combination of woodcut and wood engraving. Respectively, in 1862 and 1881, caricatures first appeared in ‘Hutum Painchar Naksha’and ‘Bangabashi’ newspaper in woodcut. In the last quarter of the 19th-century, single-sheet woodcut prints began to be produced independently. As a result, an indigenous relief printmaking school emerged in North Calcutta, popularly called the ‘Bat-tala’ reliefs. The engravers of Bat-tala, using jewellery needles, put their traditional skills to new use, to produce black and white relief prints on cheap paper. Their unique approach, decorative textures, and lack of shading and volume, were significantly different from the European academic style. Images of deities, mythological pictures, social pictures, and other popular imagery are represented in Bat-tala reliefs in an admixture of Bengali folk and British academic style.

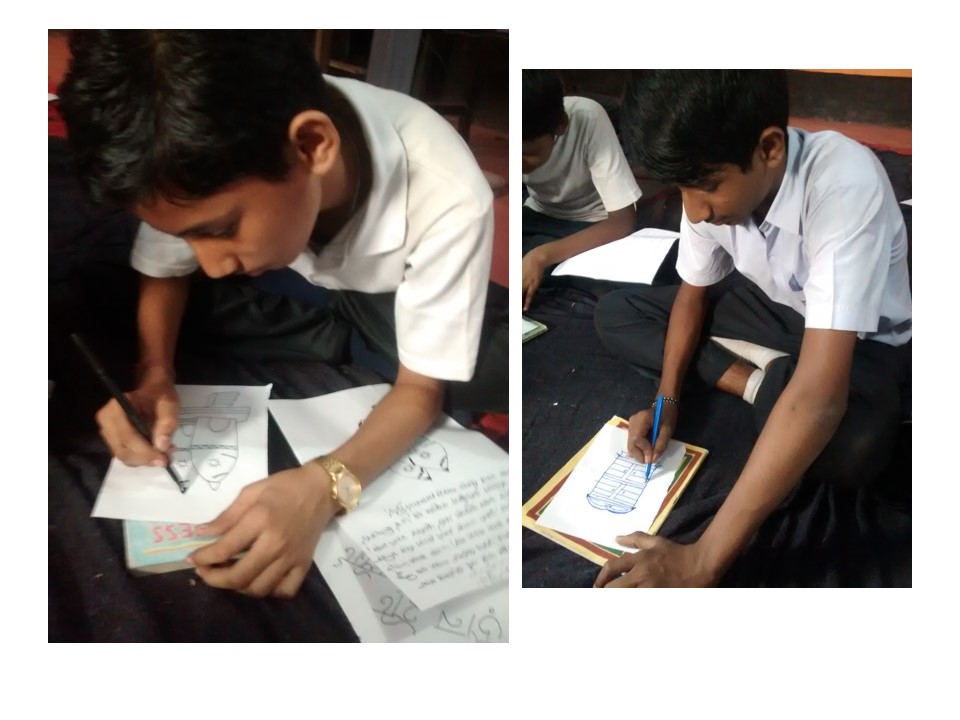

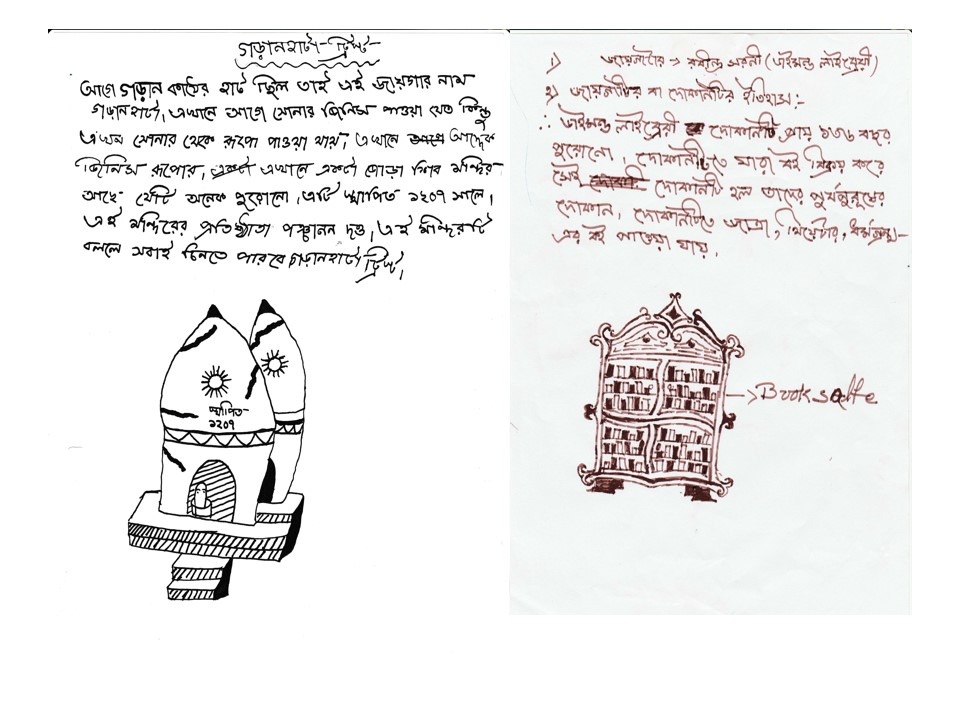

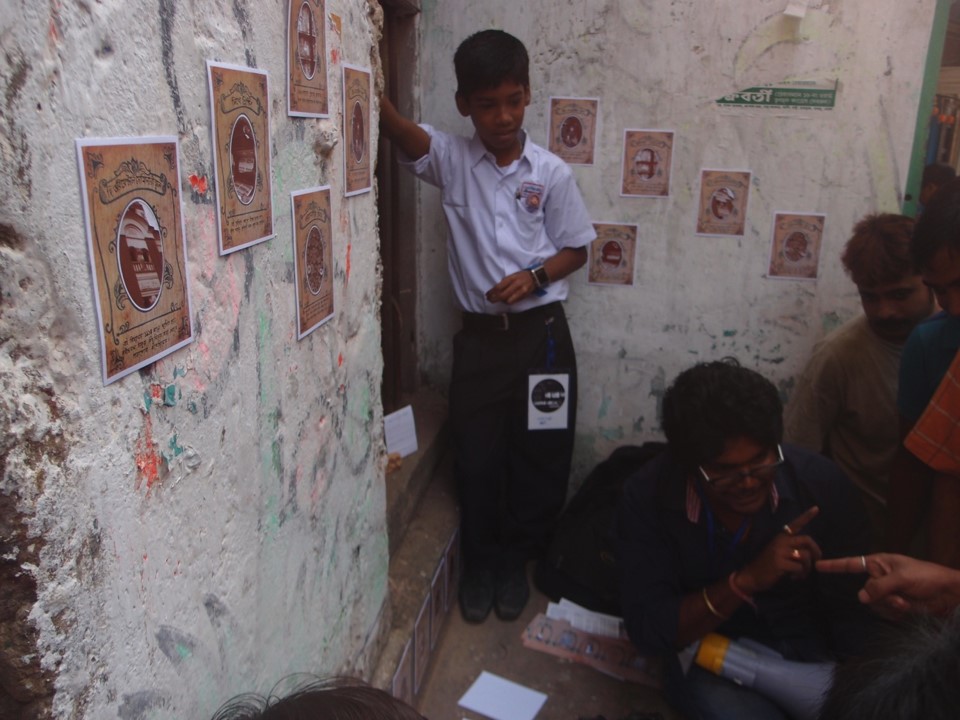

The project began in collaboration with Class 6 and 7 students of Oriental Seminary School. Together, we explored the neighborhood to uncover local histories and stories. After each walk, the students returned to school to write and draw the stories they had collected. Over time, these narratives and illustrations were carefully developed into a series of story–image pairs.

Through discussions with the students, these stories were eventually transformed into a memory game.

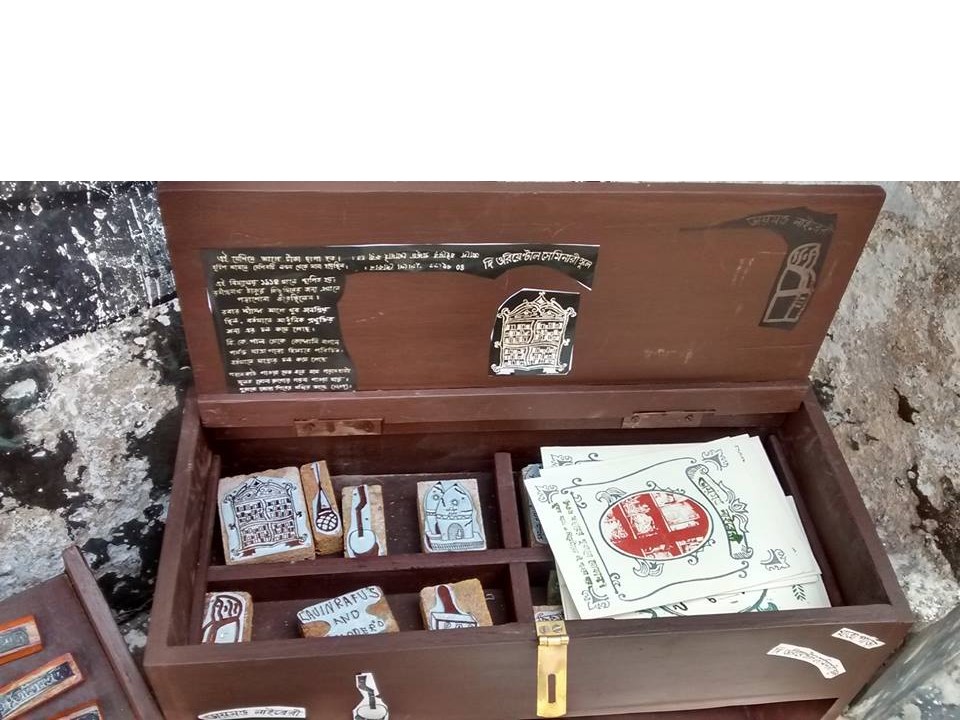

The cards were designed and then printed in collaboration with local craftsmen and printers, using wood engraving blocks, rubber stamps, and serigraphy. Since wood engraving and rubber stamp printing are processes that are gradually disappearing, the project also aimed to revive and celebrate these traditional techniques.

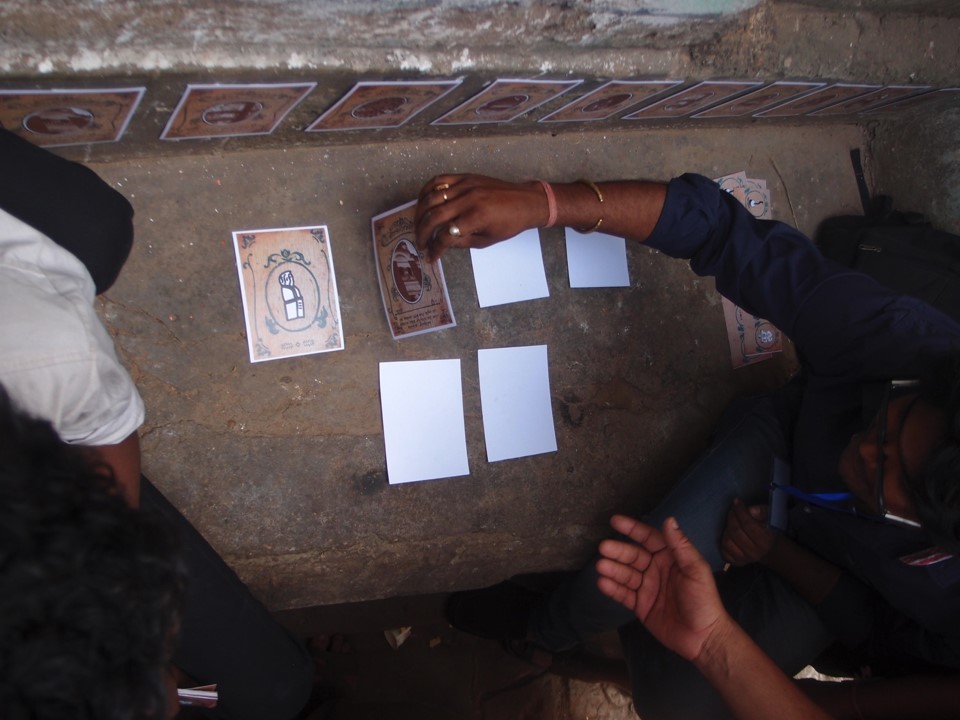

Once the cards were ready, we designed a mobile box to carry the entire game. With this, we began moving around the neighborhood, playing the game in public spaces such as teashops, rok (street corners), courtyards, and other public gathering spots.

The game quickly drew the attention of local residents, sparking conversations and interactions.

Women from the neighborhood also joined in, challenging the traditionally male-dominated nature of public spaces like tea stalls and street corners. In this way, the project helped blur and reshape existing social boundaries through play and dialogue.