The Bijoy Krishna Girls College, also popularly known as Howrah Girls College, was founded by Prof. Bijoy Krishna Bhattachrya in 1947.

Bijoy Krishna was an Indian independence activist and social worker who aimed to promote and provide higher education for women. Renowned Bengali poet Jibananda Das and novelist Bani Basu served as esteemed professors at this institution.

In 2019, I joined the Department of B.Ed. at Bijoy Krishna Girls College, Howrah, as a guest faculty. As one of the prominent women’s colleges in Howrah, numerous events focusing on women’s empowerment, including special talks, lectures, and seminars on social and legal rights, were held concurrently. Alongside my regular fine art classes, I took on the responsibility of designing posters and banners for these events.

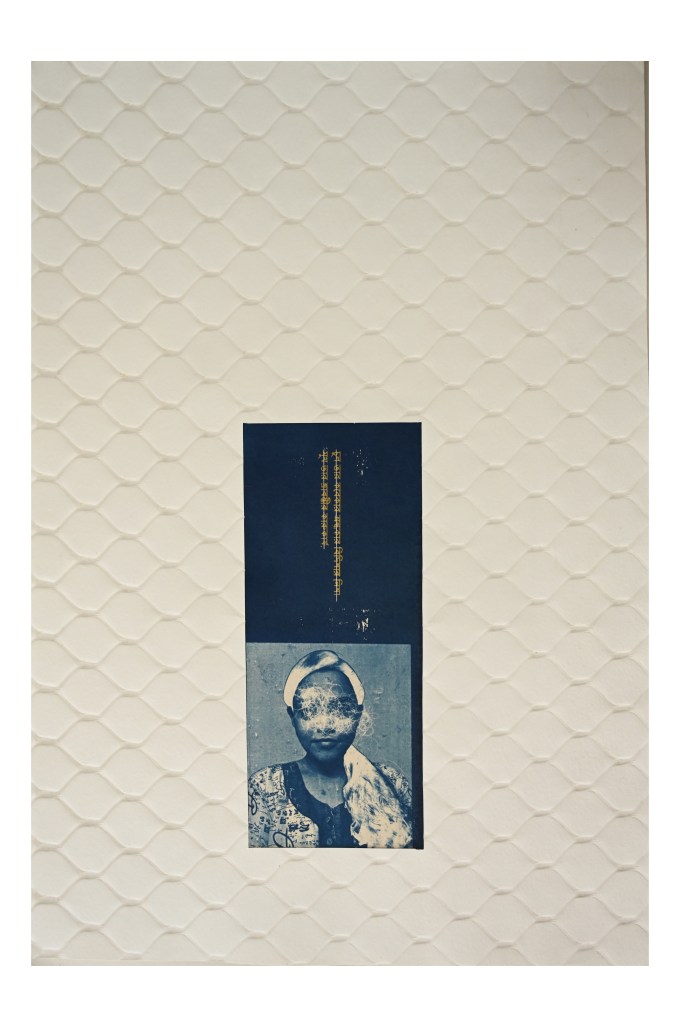

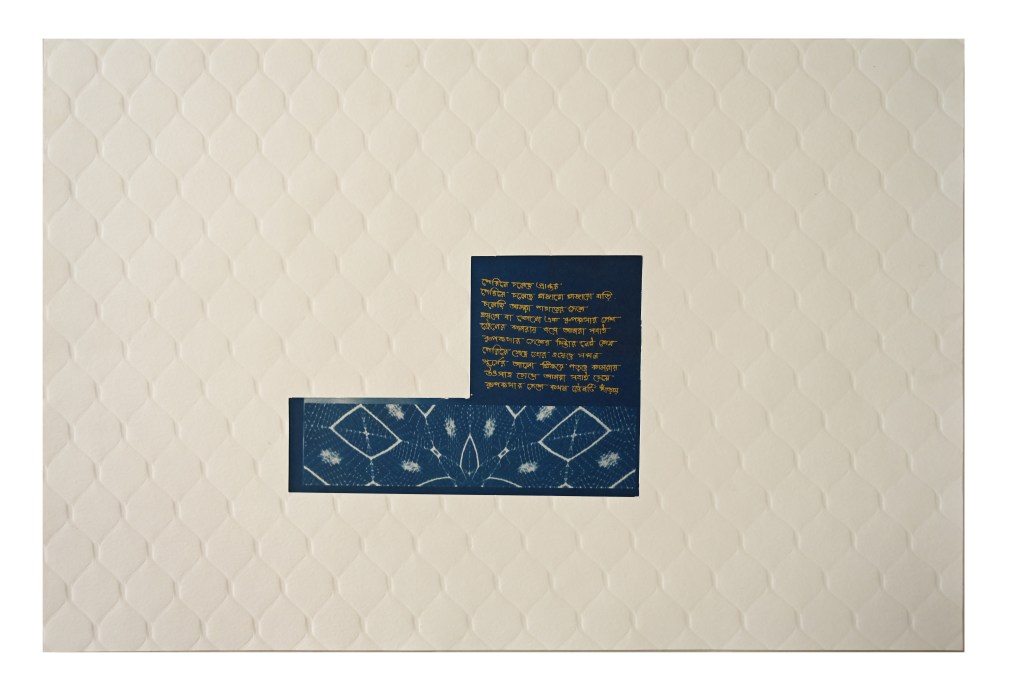

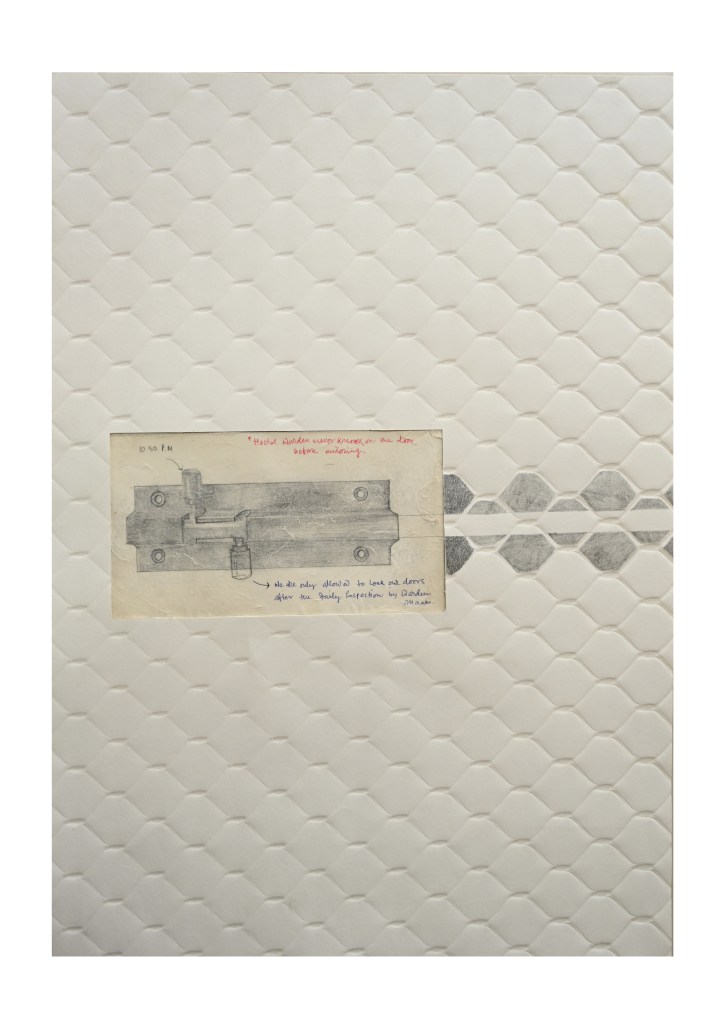

As I navigated through the vibrant activities on campus, my attention was involuntarily drawn towards the women’s hostel. Named after Jibanananda Das’s poignant poem Banalata Sen, the hostel seemed to exude a sense of literary grace. However, the imposing metal fence encircling its courtyard casts a somber shadow over its surroundings. It felt like a barrier, isolating the hostel from the rest of the college. Jibananda Das rose to prominence as a literary figure, marking a significant departure from the stylistic conventions established by Rabindranath Tagore. While credited with heralding the modern era in Bengali literature, Das’s poem Banalata Sen presents a conventional portrayal of women’s beauty, emphasizing attributes like long-dark hair, and a beautiful face like stone sculpture of Shravasti. In contrast, novelist Bani Basu, who also served as a professor at the college, penned several feminist novels, including noteworthy works like Swet Pathorer Thala and Gandhari: The Life of a Musician. Immersing myself in these literary works and conducting research has led me to contemplate the necessity of imposing fences around the women’s hostel. As a male teacher, I wonder whether such boundaries are imposed in a male hostel.

As a result, I began questioning fellow faculty members, various administrative bodies such as IQSE, and college authorities about the necessity of the fences surrounding the women’s hostel. Despite the hostel’s location within the secure confines of the college campus, protected by towering walls and vigilant security at the entrance gates, I was consistently met with silence when I tried to find a logical explanation for these barriers. Not getting feedback from the teachers and administration I thought of interviewing students. A resident student of the hostel shared her mixed thoughts about the fencing around the hostel during the interviews. She acknowledged that she didn’t enjoy them, but that they gave her a sense of security. I was curious, so I inquired, “Safe from whom?” She disclosed that because of the college’s close proximity to the market and Howrah railway station, drunk people frequently wandered around the area at night. One of the non-border students who lives in the suburbs told me she never wanted to stay inside the hostel because it looked too claustrophobic for her, but she also said she feels like she’s living in a hostel even in her own home. Because of her gender, she is not permitted to come late at night or go anywhere with her friends after college hours, and her parents intend to marry her as soon as her studies are completed.

These interactions were truly eye-opening for me. I understand that these iron fences are not physical boundaries installed in this specific geographic location, but rather something deeper rooted in patriarchal social classification. These realizations prompted me to reflect on my responsibilities as a teacher. I have begun working on a number of mixed-media pieces, animated films, and interactive installations. These works explore the boundaries of femininity, masculinity, and intimacy in the larger context of gendered space.

Medium – Cyanotype, emboss, serigraphy, graphite, pen and mirror